Legislation

The legislation governing data protection in the EU and Estonia is outlined here.

European and International law opens in a new tab

Public Information Act opens in a new tab

Personal Data Protection Act opens in a new tab

Electronic Communications Act opens in a new tab

The website of Riigi Teataja.

EDPB-EDPS JOINT OPINION 1/2026

On the Proposal for a Regulation as

regards the simplification of the

implementation of harmonised rules on

artificial intelligence (Digital Omnibus on

AI) https://www.edpb.europa.eu/system/files/2026-01/edpb_edps_jointopinion_202601_proposal_ai-omnibus_en.pdf

Adopted on 20 January 2026

Cross-border data protection impact assessment list

In case of cross-border data processing (see GDPR art. 35 (6)), the aspect of large scale processing shall not be defined by exact minimum number of data subjects. Therefore, the data controllers needs to adhere to the following requirements when conducting cross-border personal data processing.

The following list is indicative and given examples complement and further specify the requirement set out in Art 35(1) of the GDPR and the criteria listed in the WP248 “Guidelines on Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA) and determining whether processing is „likely to result in a high risk“ for the purposes of Regulation 2016/679”.

Data protection impact assessment needs to be done by every data controller, when taking into account the nature, scope, context and purposes of the processing there is the likely outcome of a high risk to a natural person.

The GDPR (art 35 (3)) provides three examples of this.

- The first example is about profiling – the data controller/processor evaluates natural persons:

a. by using automated processing

b. extensively (large scale)

c. systematically and

d. this kind of evaluation produces legal effects to concerning natural person or significantly affects the natural person.

- The second example is about processing special categories of data or data about criminal convictions on a large scale.

- The third example is about systematic monitoring of a publicly accessible area on a large scale.

Based on the WP243 and WP248 Guidelines, following factors should be considered when determining whether the processing is carried out on a large scale:

a. the number of data subjects concerned, either as a specific number or as a proportion of the relevant population;

b. the volume of data and/or the range of different data items being processed;

c. the duration, or permanence, of the data processing activity;

d. the geographical extent of the processing activity.

Examples listed in Art 35(3) of the GDPR are not exhaustive. Therefore, other kind of personal data processing, that might pose a high risk comparable to the previous three examples, also need the data protection impact assessment.

For instance:

4. Processing of biometric data for the purpose of uniquely identifying a natural person, on a large scale.

5. Processing of genetic data, on a large scale.

6. Processing in the context of employment that involve systematic monitoring of employees activities, on a large scale.

Large scale processing, that:

Might pose a risk of identity theft or fraud (particularly in digital trust services and in comparable identity management services).

Might pose a risk of property loss (particularly in banking and credit card services).

Might pose a risk of violation of secrecy of correspondence (particularly in communication services).

Involve tracking of location in real time (particularly in communication services).

Might pose a risk of disclosure of personal economical stand (particularly taxation data, banking data, credit ranking data – publicly available data is not taken into account).

Might pose a risk of discrimination with legal consequences or with similar impact (particularly in labor broking services and in assessment/evaluation services having impact on salaries and career).

Might pose a risk of loss of statutory confidentiality of information (restricted information, professional secrecy).

We emphasize that previously mentioned lists and examples are not exhaustive, as examples in GDPR art 35 (3) itself are not exhaustive.

Last updated: 16.01.2024

How can we help foreign persons and authorities

Who we are and how can we help you?

Who we are

Estonian Data Protection Inspectorate is national supervisory authority according to:

Personal Data Protection Act opens in a new tab

Public Information Act opens in a new tab

Electronic Communications Act opens in a new tab

Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation).

EU Directive 2002/58/EC opens in a new tab on privacy and electronic communications.

Directive (EU) 2016/680 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data by competent authorities for the purposes of the prevention, investigation, detection or prosecution of criminal offences or the execution of criminal penalties, and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Council Framework Decision 2008/977/JHA.

Council of Europe Convention 108 opens in a new tab on automatic processing of personal data,

Council of Europe Convention 205 opens in a new tab on access to official documents (not yet in force).

We can help you if

Your privacy rights are violated in processing of your personal data;

It also covers problems of granting access to your personal data in Schengen and Europol databases;

You have problems with spam messages;

You are refused to access to Estonian public sector information.

Taking action

Majority of cases are about ongoing unlawful processing of personal data where our goal is to eliminate violation by warning or by coercion.

On cross-border cases we also cooperate with corresponding foreign authorities.

Please see relevant legislation and guidelines for further insight.

When we cannot help you

Crimes like intentional identity theft – you should turn to police;

Slander, other private disputes and compensation for damage – you should turn to civil court;

How to reach

Request – asking general advice, interpretation of the law.

Complaint – seek protection of your violated privacy rights.

Challenge – grant access to Estonian public sector information after denial.

Forms

You can contact us in writing, by e-mail or through the e-environment opens in a new tab.

When submitting a request in writing or by email, you can use the file-based sample form. In this case, the request for clarification must be sent to the e-mail address info[at]aki.ee. Written application to the postal address Tatari 39, 10314, Tallinn, Estonia.

Request form | 14.44 KB | docx

When submiting a complaint or challenge in writing or by e-mail using a file-based sample form. In this case, the application must be sent to the address info[at]aki.ee or to the postal address Tatari 39, 10134, Tallinn, Estonia.

Complaint form | 18.13 KB | docx

The application for intervention must be (digitally) signed.

You can submit an intervention request to us on behalf of another person if you have their power of attorney or are their legal representative: for example, a parent or guardian.

Language

According to the Adminsitrative Procedures Act §20 the language of administrative proceedings shall be Estonian.

Complaints and challenges must be submitted in Estonian. In individual exceptional cases, we accept clarification requests in English and you can expect answers in English as well.

For cross-border cooperation between authorities we use English.

Deadline

We handle questions, complaints and challenges within 30 days. Handling complaint can be extended to another 60 days.

Publication of decisions

According to law we publish our precepts and decisions on our website without personal and other restricted data.

Last updated: 17.07.2024

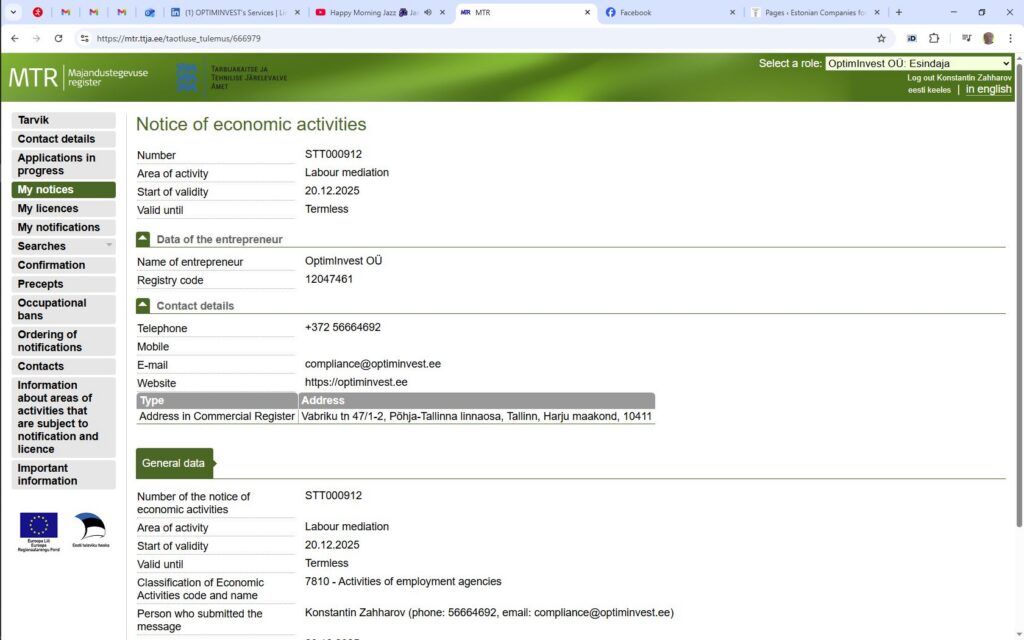

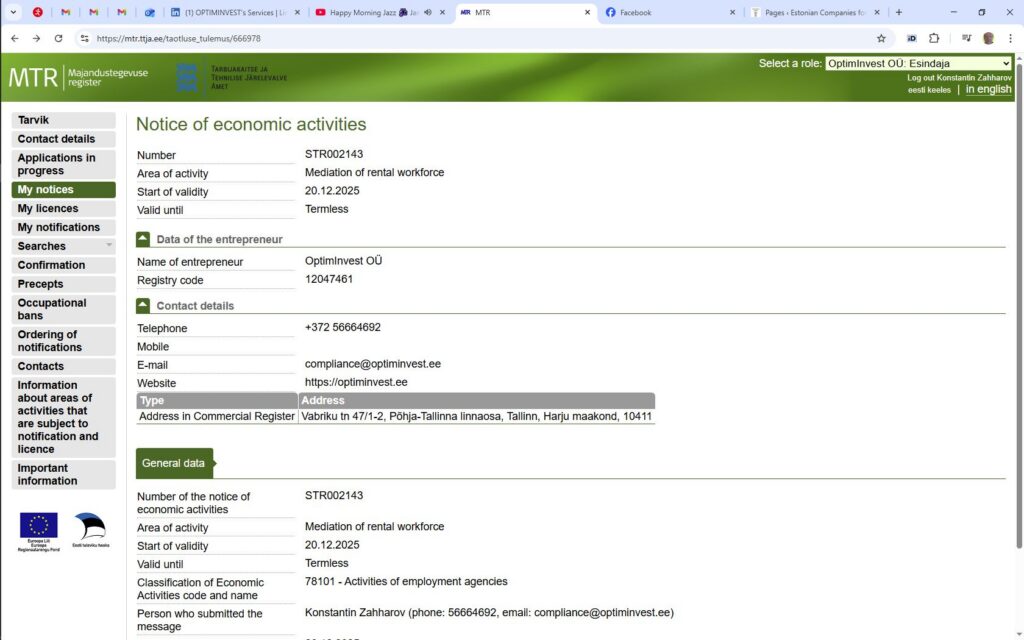

Since 1 July, 2014 Estonian FIU issues authorisations for operating in the following areas of activity:

- operating as a financial institution

- providing trust and company services

- providing pawnbroking services

- buying-in or wholesale of precious metals, precious metal articles or precious stones, except precious metals and precious metal articles used for production, scientific or medical purposes

Until the end of 2024 the FIU issued authorisations for providing virtual asset services. Currently, Finantsinspektsioon opens in a new tab issues these licences.

Applying for authorisation

This page contains information about applying for authorisation

The application for authorisation can be submitted in the register of economic activities, which can be accessed:

- via the state portal Eesti.ee opens in a new tab

- via the website opens in a new tab of the register of economic activities

(services – for an entrepreneur – licences and registrations – Entering the Register of Economic Activities)

Estonian Financial Intelligence Unit Analysis Reveals Systemic Deficiencies in the Crypto-Asset Sector

04.12.2025 | 11:56

Estonian Financial Intelligence Unit Analysis Reveals Systemic Deficiencies in the Crypto-Asset Sector

The Financial Intelligence Unit (FIU) has identified a systemic risk area among virtual asset service providers related to the identification of correspondent relationships and the implementation of due diligence measures. In conducting the study, the FIU consulted with the U.S. Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN), which made contributions to the findings.

The analysis revealed that nested virtual asset services allow smaller providers – including those operating from jurisdictions with weak supervision or lacking a valid license – to operate through larger service providers. By publishing the results, the FIU aims to raise awareness among market participants and law enforcement authorities about how cryptocurrency exchanges and their nested services can be exploited for criminal purposes.

“Estonia was among the first countries to start issuing licenses for the provision of virtual asset services. In 2021, there were more than 600 valid licenses, whereas today there are 37. This experience has given us extensive information about service providers – knowledge that can also benefit other countries,” said Markko Kard, Deputy Head of the Estonian FIU. “During the analysis, we observed many virtual asset service providers operating anonymously, failures to apply due diligence measures, legal entities incorrectly registered as natural persons, multi-layered nested structures resembling Russian nested dolls, and many other practices that do not comply with anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist financing standards,” Kard explained.

The study conducted an in-depth analysis of transactions by 12 virtual asset intermediaries and their correspondent relationships with licensed crypto platforms. Millions of blockchain data points and publicly available information were used for this purpose. The findings were also compared with data from the FIU’s database.

The main outcome was the identification of red flags related to the concealment of legal entity ownership structures and beneficial owners, the location and country of registration, shortcomings in risk management, and blockchain or service model characteristics. Taking these red flags into account will help virtual asset service providers better identify correspondent relationships and determine when enhanced due diligence measures are required.

The Estonian FIU was established in May 1999 within the Police Board. In January 2021, it became an independent government agency under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Finance. Strategic analysis of money laundering and terrorist financing risks, threats, trends, patterns, and typologies is a statutory function of the FIU.

National Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing Risk Assessment 2025

10.11.2025 | 14:37

National Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing Risk Assessment 2025

The Ministry of Finance has published a new national risk assessment on money laundering and terrorist financing, which indicates a medium level of money laundering risk in Estonia. The assessment is based on data from the years 2020–2024.

Sectors with a higher-than-average money laundering risk level include credit institutions, payment and e-money institutions, virtual asset service providers, gambling operators, and corporate service providers. A higher risk rating means that market participants in these sectors must pay increased attention to anti-money laundering (AML) measures and apply enhanced due diligence.

The risk level has risen in connection with companies registered in Estonia but with weak ties to the country, often managed by foreign nationals. A higher threat and vulnerability level is also linked to gambling operators holding Estonian licenses, whose number has doubled over the past five years. Cash-intensive sectors such as casinos, catering, and real estate continue to pose higher money laundering risks.

According to the risk assessment, the main predicate offenses were fraud (especially business email compromise schemes, or BEC frauds), as well as tax and drug-related crimes. Companies registered in Estonia are often used to commit crimes abroad, particularly in cases of tax offenses. Most money laundering cases analyzed during the assessment period involved the layering stage, in which criminal proceeds obtained abroad were moved through the Estonian financial system.

Money laundering primarily occurs through bank transfers, fictitious invoices, and loan agreements, but the use of virtual assets is increasing. In addition, there has been growth in so-called money laundering service provision, where criminal networks use intermediaries to conceal the origin of assets.

The risk of terrorist financing remains generally low, though threats arise from foreign sources, particularly Russia, as well as cross-border transactions and the use of virtual assets.

The risk assessment was prepared by the Ministry of Finance in cooperation with the Financial Intelligence Unit, law enforcement and supervisory authorities, the Ministry of Justice and Digital Affairs, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and the Ministry of the Interior. At the national level, this represents the largest risk assessment project in Estonia. Over one hundred public sector experts participated, alongside representatives from the private sector.

The national risk assessment forms the foundation of Estonia’s AML/CFT system, ensuring a risk-based approach. It serves as the main tool for systematically and evidence-based identifying risks, directing resources efficiently, ensuring compliance with international standards, and supporting awareness and accountability across both the public and private sectors in combating money laundering.

Next, an action plan will be developed to ensure that the conclusions and recommendations of the risk assessment lead to concrete risk mitigation measures.

The Governmental Commission for the Prevention of Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing approved the three-part risk assessment report on 30 September, and the full report is available on the Ministry of Finance’s website. opens in a new tab

The risk level defined in the assessment depends on the interaction between threats and vulnerabilities. A threat is an event or activity pattern indicating the possibility that financial criminals might exploit Estonia’s economic environment and financial system to launder criminal proceeds. Vulnerability refers to weaknesses in the set of AML measures that make up the anti-money laundering framework.